The La Garçonne Style of the 1920's

“Tu es beau, toi aussi!” (Translated: Well, you’re handsome, too!)

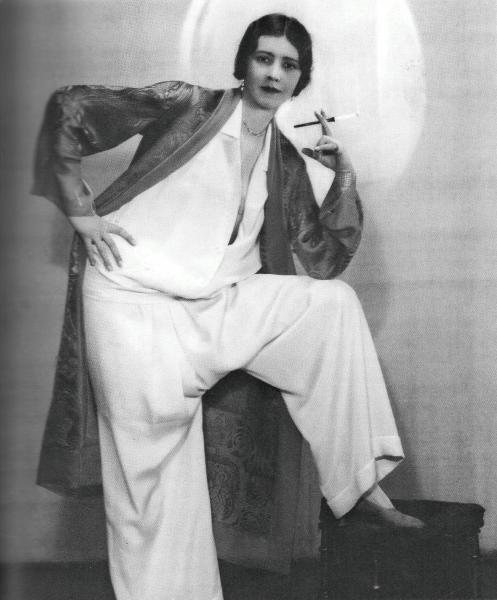

Turning heads with their fresh bobs and pushing the societal limits of fashion was the norm for the modern and sophisticated 1920’s woman.

Unnerving to the traditionalists, this new fashion aptly entitled "La Garconne" also brought with it flashes of androgyny and masculinity: ties, colorful neck scarves, high-waisted trousers, hats, and dresses tailored to resemble suits hung loosely from slender necks and dainty frames.

But it wasn’t all about “La Garçonne''

In fact, mixed with these minimal layers of wool and cotton, highlighting boyish attributes, you would typically spy a long, illustrious string of pearls, a plum or raspberry, deep red pout on the lips, and have your senses overwhelmed with the demure essence of floral scents. :: cue the entry of perfumes like Chanel No.5, rich with notes of lavender, jasmine, and sandalwood.

Suzanne Lenglen and Julie Vlasto playing tennis in a "la garconne" style

Suzanne Lenglen and Julie Vlasto playing tennis in a "la garconne" styleFrida Kahlo, the famous painter and muse of Diego Rivera, was a pioneer of this new, boyish style.

In 1924 a family photo shows her with her hair slicked down and parted in the middle, adorned in a full button-up suit and tie, standing in a proud and fierce stance next to her father with her hand in her pocket like a young gent. This was a perfect example of a "La Garconne" Style

The afforementioned Frida Kahlo family photo at age 16 in 1924 looking dapper

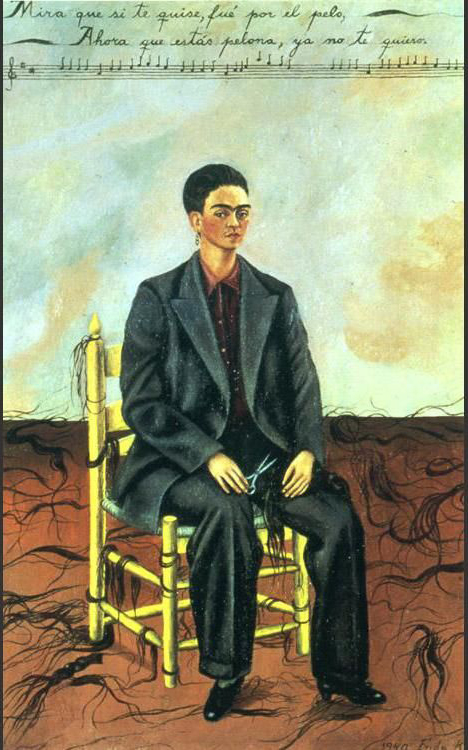

The afforementioned Frida Kahlo family photo at age 16 in 1924 looking dapperLater on in her life, after her divorce from Diego, this look even influenced and infiltrated one of her most famous paintings entitled “Self Portrait with Cropped Hair” in which she is sitting upright with a defiant stare in a chair with a baggy men’s suit on, scissors in hand, her hair self-shorn and chopped to her scalp. Critics say the painting reflects her desire to reflect independence and self-reliance, characteristics fixed by the period’s style.

La Garconne Style Permeates the 1920's Culture

Aviation, racing, and even boating were common themes found in 1920’s “La Garçonne '' fashion. It wasn’t just Amelia Earheart that donned head caps and fabrics made to soar. Other female pilots such as Ruth Elder, Florence Klingensmith, Ruth Nichols, and Louise Thaden took to the skies inspiring the looks of women at glamorous parties and in the streets. The Bruck-Weiss Gatsby-esque aviation hat lined in sequins is a perfect example of this borrowed style.

An aptly entitled plane

An aptly entitled planeIn his work, Flapper: A Madcap Story of Sex, Style, Celebrity, and the Women Who Made America Modern, author Joshua Zietz described the 1920’s woman who:

“boldly asserted her right to dance, drink, smoke, and date- to work on her own property, to live free of the strictures that governed her mother’s generation.”

This blatant desire for independence and abstract modernism shocked mothers who had spent their days tending respected households and focusing on all that was right, religious, and proper in their conservative worlds. This difference in attitudes forced mothers and daughters into a relationship highlighted by both restraint and rebellion.

Whether it was with a side-swept or short bang or a fashionable cigarette holder and shortened skirt and tie combo, women of the 1920’s knew how to infuriate their mothers and grandmothers and the La Garçonne style was an apt way to achieve this.

Taking on these habits, fashions, and characteristics more often associated with men wasn’t about glorifying them in any way- it was about glorifying a newfound female power, the power to choose what to wear for yourself rather than to be put on a pedestal and admired.

The avant-garde nature and actions of these “New” women who had now seen and survived war reflected a changing of the guard, an “I can do that too” approach to garments, accessories, and even life.